Homemade vs Store-Bought Juice: Nutrition Facts, Hidden Costs, and Recipes

Juice is big business. According to Statista Market Insights, global juice consumption is expected to reach more than 36 billion liters in 2025.

Despite its healthy image, store-bought juices aren’t always as nutritious as they look. Many are packed with added sugars, low in fiber, and stripped of nutrients during processing. And they don’t come cheap. A premium juice from a chain like Jamba Juice can cost over $10 a serving, while you can make something similar at home for under $3.

When you make your own juice, you control the ingredients, avoid added sugars, and reduce waste from plastic bottles and cartons. You’ll save money over time and potentially get more nutrients in your glass.

In this article, we’ll walk through the real benefits of fresh juicing, how much you could save, and what to consider when choosing a juicer. If you’re thinking about making juice at home, this guide covers everything you need to know.

The Nutrition Battle: Fresh vs. Processed Juice

According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, about 90% of adults don’t eat enough vegetables, and 80% fall short on fruit. A daily glass of juice can help fill some of those nutritional gaps, especially when it’s made at home using whole ingredients.

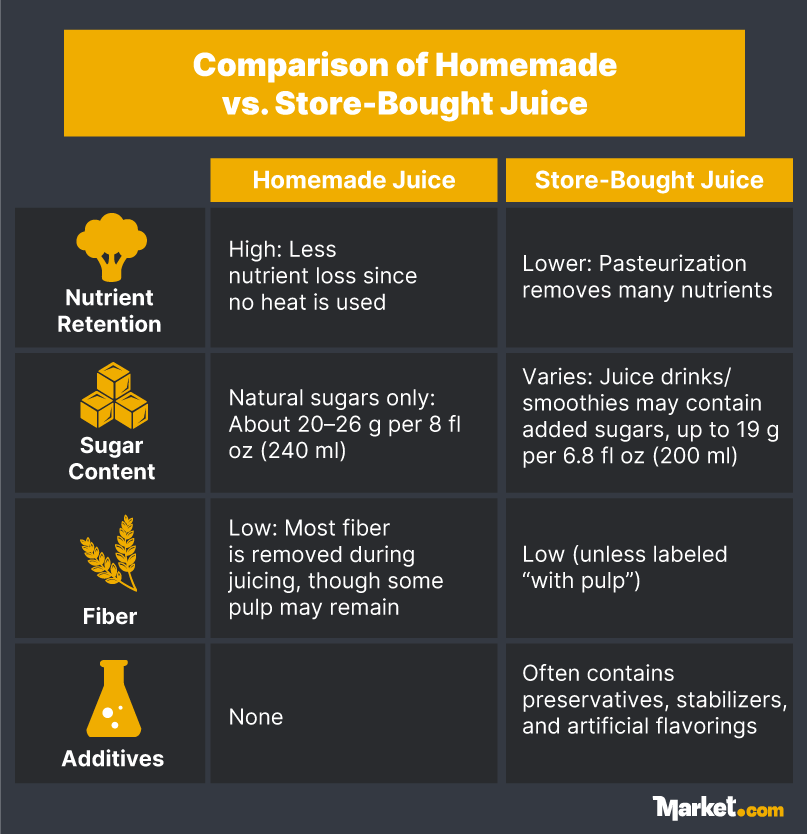

That being said, not all juice is the same — the way juice is made can have a big impact on its nutritional value. Here’s how fresh, homemade juice compares to what you’ll find on store shelves.

How Processing Affects the Nutritional Value of Juice

Store-bought juices go through a variety of processes to make sure they’re safe to drink and have a longer shelf life. This includes pasteurization, where the juice is heated, typically to between 160°F and 180°F (71°C to 82°C). This helps to kill potentially dangerous bacteria, but introducing heat can also affect the juice’s nutritional profile.

Vitamin C is sensitive to heat. Studies show that pasteurization can reduce vitamin C levels in juice by up to 90%, depending on temperature, oxygen exposure, and for how long it’s been heated. In one study, watermelon juice lost nearly all of its vitamin C after 10 minutes of heating, while mango juice retained about 73%.

Heat also destroys enzymes and antioxidants. Enzymes break down nutrients while antioxidants help to protect your cells from harmful free radicals or unstable molecules that build up in your body due to stress, pollution, poor diet, or even normal metabolism.

Fresh, homemade, or cold-pressed juices tend to retain more of the original nutrients because they’re not exposed to high heat. That includes vitamins, enzymes, and natural antioxidants like flavanones.

One study found that fresh juices stored up to 92% of their original vitamin C levels when kept in the fridge for 48 hours — a big difference compared to shelf-stable juice.

How Much Added Sugar Is Found in Store-Bought Juices?

Whether homemade or store-bought, fruit juices are generally high in sugar. The difference is where this sugar content comes from.

In pure fruit juice, whether made at home or bought from the store, the sugar comes from the fruit itself. Although there are no added sweeteners, the sugar content can still be high; for example, an 8 fl oz (240 ml) glass of fresh orange juice has about 23 grams of natural sugar — the same as a soda.

A study of 203 products sold in UK supermarkets found that fruit juices, juice drinks, and smoothies have an average of 7 grams of sugar per 3.4 fl oz (100 ml). Smoothies had the most sugar, at around 13 grams, while juice drinks had the least, at about 5.6 grams.

Over half of the products would have triggered a red nutritional warning under UK guidelines. What’s more, 85 of them had 19 grams or more per 6.8 fl oz (200 ml), which is the total recommended daily intake for children.

While store-bought juice and whole fruit might contain similar amounts of natural sugar, the key difference lies in what else you’re getting. Whole fruit provides fiber, water, and a range of micronutrients that help slow sugar absorption and support digestion. Juice, especially when made from concentrate or purée, lacks most of that fiber and often delivers fewer vitamins, making it less filling and easier to drink more sugar than you might realize.

The Case for Vegetable Juice

One way to reduce sugar while keeping your juice nutrient-dense is by adding more vegetables. Many juicing guides recommend the 80/20 rule — using about 80% vegetables and 20% fruit. This can help lower overall sugar content while increasing fiber, antioxidants, and essential nutrients.

Vegetable juices also come with proven health benefits. A 12-week clinical trial found that drinking 8 to 16 ounces of vegetable juice daily helped participants meet the recommended intake of 4 or more servings of vegetables per day, something most failed to achieve with dietary advice alone.

What Juice Labels Really Mean

Juice labels can be confusing. Terms like “100% juice,” “juice drink,” or “from concentrate” might sound similar, but they mean very different things — and both US and EU authorities have specific rules for how they’re used.

In the US, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) says that “100% juice” must be made entirely from fruit or vegetable juice, with no added sugars, sweeteners, or artificial flavors. If the juice is made from concentrate, the label must clearly say so and note that water has been added back.

But it’s not necessarily that straightforward. A “juice drink,” for example, can contain as little as 5% juice, with the rest made up of water, sugar, or other ingredients.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in the EU takes a similar approach to the FDA, but with a few extra categories. “Fruit juice” refers to 100% juice, while “fruit juice from concentrate” means the water was removed and then added back later.

Then there’s “fruit nectar.” That’s usually a blend of juice and purée, of which up to 20% of the drink’s total volume can be added sugar or honey. These drinks can sound healthy, but they often have less juice and more sweeteners than you might expect.

Preservatives, Stabilizers, and Artificial Flavors Found in Juice

To stay fresh on the shelf for weeks or even months, many packaged juices contain added preservatives, stabilizers, and flavors. These ingredients help with shelf life and taste, but they’re not always obvious unless you read the fine print.

Some of the most common preservatives used in juice are citric acid, sodium benzoate, and potassium sorbate. All of these additives are permitted by both the FDA and the EFSA and are considered “generally recognized as safe” when used within regulatory limits.

One study found that juices with sodium benzoate and citric acid kept their flavor and color the best over time. Others, like potassium sorbate and sodium metabisulfite, were also effective, but the juice showed more noticeable changes in taste and appearance after about a week.

Flavorings are another story. Some juices use added flavors, natural or synthetic, to restore taste lost during pasteurization. In 2018, the FDA removed seven synthetic flavoring substances from its approved list after long-term animal studies linked them to cancer at high doses. EFSA had already restricted some of these earlier.

One flavor additive still commonly used in both the US and EU is ethyl vanillin, a synthetic compound used to enhance sweetness. While approved for food use, it’s also criticized for the side effects found in long-term animal studies, linking it to conditions like anemia and liver inflammation.

So, while additives may be considered safe by regulators, the overall quality and nutritional value of juices containing them can vary. It’s worth checking the label before you buy.

The Environmental Impact of Juice: Waste and Sustainability

Drinking juice has an environmental cost. When considering the packaging waste, energy use, and food processing byproducts, the impact of commercial juice production can add up pretty fast.

Packaging Waste

Store-bought juice usually comes in plastic bottles, glass containers, or Tetra Paks, each of which has its own recycling challenges.

Around 25% of used Tetra Paks — which combine cardboard, plastic, and aluminum, making them difficult to process — are recycled globally. While glass is easier to recycle, the global average still remains below 35%.

Plastic bottles are the most common packaging for juices, but among the least recycled. In 2023, only 33% of PET plastic bottles were collected for recycling in the US, and just 16% of new bottles used recycled plastic.

Most of these containers end up in landfills or waterways, where they threaten wildlife and pollute ecosystems.

Carbon Footprint

Making and bottling juice takes a surprising amount of energy. According to data from one major juice brand, producing a 30 fl oz (900 ml) bottle of orange juice can generate around 900 grams of carbon emissions.

Most of that footprint comes from ingredient transport and processing, with packaging and distribution adding further impact. Energy-intensive steps like pasteurization and vacuum evaporation also play a big role.

On average, juice processing uses 0.71 megajoules of energy per liter, which is about the same as running a laptop for 3 to 4 hours.

One study found that producing a single bottle of apple juice can require as much as 28.33 megajoules of energy. And with global juice consumption expected to reach 36 billion liters in 2025, that adds up fast.

Another way to reduce your carbon footprint is by composting unused parts of the plant, or reusing them in cooking. Juice manufacturers create 25 million tons of citrus waste alone; by making juices at home, you can be creative by using peels for zest in cooking recipes, composting any unused portions, or coming up with other creative solutions. And when you shop for seasonal, locally grown fruit, you reduce your carbon footprint even further.

Water and Resource Use

Juice production is resource-heavy. Agriculture accounts for 70% of the water used in the juice supply chain, and industrial processing accounts for another 20%.

Estimates suggest it takes nearly 1.5 liters of water to make just 1 liter of juice. Globally, the juice industry generates more than 34 billion gallons of wastewater annually, which is low in oxygen and can damage aquatic ecosystems if left untreated.

Juice also strains resources in the countries where fruit is grown. For example, the UK imports 89% of its fruit, mostly from water-stressed regions, putting further pressure on freshwater supplies.

The Cost Factor: Save Money by Making Your Own Juice

In addition to supporting your health and environmental footprint, making your own juice at home can save you a lot of money, especially if you’re drinking it regularly.

At Jamba Juice in New York City, a large orange juice can cost around $10.99 for 28 fl oz (828 ml), or about 39 cents per fl oz (33 cents per 100 ml). Homemade orange juice, on the other hand, costs just 16 cents per fl oz (13.5 cents per 100 ml) using average US orange prices and a typical yield from 1 kg of oranges.

Even when you factor in the cost of a juicer, which is typically anywhere from $75 to $500, the long-term savings of making juice at home become clear.

Let’s take a mid-range juicer, for example. At around $299, spread over the average lifetime of a juicer (around 6 years), and making three 16 fl oz (473 ml) juices a week, you’ll spend around $441 per year, including both the produce and the equipment.

Buying the same amount of juice from a juice bar like Jamba would cost roughly $1,714 per year. That’s a saving of over $1,270 annually.

Of course, how much juice you get from your produce matters, too. On average, 2.2 lbs (1 kg) of oranges will get you around 13.5 fl oz to 17 fl oz (400ml to 500ml) of juice, depending on how juicy the fruit is and the efficiency of your machine.

To cut costs further, you can shop for produce that’s in season. Citrus is typically cheaper in winter, and berries are in summer. Avoiding pricey tropical imports can also help lower your costs and carbon footprint.

Choosing the Right Juicer: What to Look For

Not all juicers work the same way. Some prioritize speed and convenience, while others focus on nutrient retention and juice yield.

Understanding the differences between models can help you choose a juicer that fits your needs, budget, and lifestyle. Below, we break down the main types, key features to compare, and tips for choosing the best juicer.

Types of Juicers

The juicer you choose can affect what you can juice, the quality of your juice, as well as how easy the machine is to use, clean, and store. Each juicer type has its own strengths and drawbacks. Here’s how the most common options compare:

Key Features to Compare

Once you’ve narrowed down the type of juicer you’re considering, it helps to compare a few core features. The performance, maintenance, and durability of the juicer can make a big difference in how often you actually use it.

- Juice yield: Masticating and twin gear juicers typically extract more juice per ounce of produce — up to 30% more than centrifugal models. This means you’re getting less waste and more value from your produce.

- Motor power and speed: Centrifugal juicers have the strongest motors and operate at the highest speeds. Masticating and twin gear models run much slower; this helps preserve more nutrients and makes it easier to juice tough greens.

- Ease of cleaning: Simplicity matters here. Centrifugal juicers usually have fewer parts, making them easier to clean. Masticating and twin gear models are more complex and difficult to wash up. Look for models with dishwasher-safe parts if easy cleanup is a priority.

- Noise level: Centrifugal juicers’ high-speed motors mean that they’re the loudest of the bunch. If noise is a major concern, you might want to go for a masticating or manual model, which are considerably quieter.

- Longevity: The average juicer lasts around 5 to 7 years, though that varies depending on build quality and how often it’s used. Centrifugal juicers tend to have shorter lifespans than masticating models.

Juicer Pricing

Juicers can cost anywhere from $50 to over $500, depending on the type and features.

Centrifugal models are usually the most affordable and cover most entry-level needs. Masticating juicers tend to fall in the $150 to $400 range, while twin gear and true cold press machines are at the higher end, usually priced for commercial or heavy-duty use.

In general, you should expect to pay more for a machine that offers a higher juice yield, quieter operation, and better durability.

Which Juicer Should You Choose?

If you’re just getting started or want something fast and simple, a centrifugal juicer may be enough. It’s low-cost, easy to use, and gets the job done quickly.

For more advanced juicers or those who want higher-quality juice with longer shelf life, a masticating juicer might be worth the investment.

Serious users, or those juicing a wide range of produce, will likely want a twin gear machine. It offers the best performance if you’re willing to trade juicing time and counter or storage space for juice quality.

7 Easy Homemade Juice Recipes to Get Started

Once you’ve picked the right juicer, the next step is making something with it. Below are seven juice recipes chosen for their variety, balance, and beginner-friendly prep. They’re designed to help you incorporate more vitamins and minerals into your day without overloading on sugar.

1. Green Power Fusion

Ingredients:

- 1 bunch celery

- 2 bunches kale

- 1 cucumber

- 2 limes

- 1 apple

- ¼ cup parsley

This recipe combines hydrating vegetables with citrus and apple for a mild, not-too-sweet green juice. It’s rich in vitamins A, C, and K, and can support digestion and immune health.

2. Carrot Orange Glow

Ingredients:

- 2 medium carrots

- 2 oranges

- 1 piece of fresh ginger

This juice is high in beta-carotene and vitamin C. It’s a good option in the morning or whenever you need a natural immunity boost. The ginger adds a small kick and some added anti-inflammatory benefits.

3. Tropical Kale Cleanser

Ingredients:

- 1 handful kale leaves

- ½ cup pineapple

- ½ cup coconut water

This juice blends leafy greens with tropical fruit and electrolytes. The kale provides a strong dose of vitamins A and K, while pineapple adds a touch of sweetness and bromelain, an enzyme known to support digestion. Coconut water helps with hydration, making this a good pre- or post-workout option.

4. CCA Juice

Ingredients:

- 1 head cabbage

- 2 large carrots

- 2 apples

Short for cabbage, carrot, and apple, CCA juice is rich in antioxidants and fiber. Cabbage supports gut health and may help reduce inflammation. Carrots bring beta-carotene, and apples offer a natural sweetness along with vitamin C. It’s a nourishing juice that works well in colder months.

5. Cucumber Apple Mint Cooler

Ingredients:

- 2 medium cucumbers

- 2 green apples

- 1 handful mint leaves

Light and refreshing, this is a great juice for warmer days or when you’re feeling sluggish. The cucumber has a high water content, mint offers a natural cooling effect, and apples give it just enough sweetness. It’s also super simple to prepare.

6. Carrot Wheatgrass Energizer

Ingredients:

- 2 medium carrots

- 1 small handful wheatgrass

- 1 cup blueberries

- 1 stalk celery

If you’re looking to boost your energy naturally, this juice offers a mix of vitamins, minerals, and plant compounds. Wheatgrass is nutrient-dense, though its flavor is strong, so the carrots and blueberries help balance that out. Celery adds hydration and a mild salty note.

7. Watermelon Blueberry Hydrator

Ingredients:

- 2 cups watermelon cubes

- ½ cup blueberries

- 1 tablespoon lime juice

While fruit-only juices are usually best in moderation, this one is a light, hydrating exception. Thanks to the high water content of watermelon and the modest portion of blueberries, it’s low in sugar and ideal for hot weather or post-exercise rehydration. The lime adds a subtle, refreshing kick.

Final Thoughts

Juice might look simple, but a lot is going on behind the label. Between added sugars, preservatives, nutrient loss, and plastic packaging, that store-bought bottle might not be giving you as much as you think.

Making juice at home is one of those small habits that can add up to a lot. You get more control over what goes into your glass and avoid added sugars and preservatives, reduce plastic waste, and keep more nutrients intact. Plus, it’s usually cheaper in the long run, especially if you juice regularly or use produce that’s in season or already in your fridge.

Homemade juice doesn’t have to be complicated either. With a few basic ingredients and a reliable juicer, you can build a routine that does your health a favor, saves you money, and gives the planet a break, too.